Prison or Protection?

An Essay on Simon Denny’s “Amazon Worker Cage”

This essay explores the work of artist Simon Denny, which in the age of datafication and Industry 4.0 serves as a seismograph for the potential consequences of digital transformation, and urges us to consider the consequences of data capitalism and workplace surveillance. I reflect on Denny's 'Amazon Worker Cage', which is based on an original Amazon patent and critically addresses implications such as job loss and the dehumanisation of labour. It was originally designed as a safe means of transport for a human worker in an automated environment where robotic systems do most of the work. Denny's interpretation, however, exposes it as an architectural inversion of panoptic surveillance (i.e. a "guard" in the centre, the "guarded" around the centre) and creates a thought-provoking execution of the original patent that is best interpreted in light of the evolution of labour management from Taylorism to Foucault's "disciplinary society".

The 21st century is often referred to as “the age of information”. Be it while shopping in public spaces, while using social media or when jogging in the city park: Chances are high that our behaviour is being monitored and translated into data. But what actually is “data”? A definition in the Cambridge dictionary captures what most types of data have in common. According to this definition, data is: “information in the form of text, numbers, or symbols that can be used by or stored in a computer”. (“Data”, n.d.).

The collection of data is the modern-day gold rush: The extraction and selling of data is so profitable that some go as far as to refer to “data-capitalism” (West, 2017). The purposes to which data is collected are diverse. Collateral “metadata” from social media platforms is often collected without clear and distinct purpose but rather stored in anticipation of a future use. Simpler forms of collection of behavioural data, often achieved through CCTV in the public sphere, serve to ensure that citizens act in a desired manner or refrain from acting in an undesired manner. This principle of installing order by means of surveillance is taken to extremes in China, where mass surveillance enables the state to control the entire society; anytime and anywhere (Keegan, 2019).

The collection of personal data and associated surveillance at the workplace is a phenomenon that is worthy of our attention and consideration as it affects more and more people. An exhibition of the work of artist Simon Denny, currently at display in the K20 Museum in Düsseldorf, references the issue of surveillance at the workplace in its very title, “Mine”: On the one hand, the word represents the extraction of a resource. On the other hand, it signifies the possessory claim and ownership of an individual. Lastly, the mine is one of the most prominent examples of employment relations in capitalistic systems. Denny’s oeuvre conveys his critical position on data-capitalism and his artworks provoke many questions with regard to developments such as datafication and mass surveillance. This essay considers Denny’s position on surveillance at the workplace and the potential replacement of human workers by robots as expressed in his piece “Amazon Worker Cage”. To contextualize his work and bridge the agenda of surveillance at the workplace with the dawn of automated factories, a historical perspective on the evolution of the conditions of human labor is introduced first.

In her book “In the age of the smart machine: The future of work and power” (1988), sociologist Shoshana Zuboff proclaims that “Techniques of control in the workplace became increasingly important as the body became the central problem of production”, thereby referring to an important thinker of the 20th century: “[…] Michel Foucault has argued that these techniques of industrial management laid the groundwork for a new kind of society, a “disciplinary society”, one in which bodily discipline, regulation and surveillance are taken for granted.” (Zuboff, 1988, p. 319). Foucault’s argument is best understood in light of the working conditions in the industrialized countries at the end of the 19th century.

“‘So tired!’ is the cry of thousands of men, women and young persons at the close of the working day. How to meet the complaint and to remove its cause are among the problems of the present age. It would seem as if the stress of modern times was becoming too great, and as if the strain of industrial methods through improved machinery was becoming more than human strength can bear.” (Oliver, 1914, as cited in Blayney, 2017)

One promising solution to this problem was what was referred to as "Scientific Management". Scientific management developed towards the end of the 19th century, during the first heyday of the steadily accelerating process of industrialization. The engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor established certain principles, such as the division of production processes into the smallest possible units, in order to establish standardization and ensure maximal productivity. Scientific management thus bases on the principle of using data extracted from real work processes to instruct employees how to optimize their labor. The stopwatch became the new measure of things. Henceforth, understanding how individual tasks link into the greater whole was reserved to that level of operation which today we refer to as “management”. The common “blue-collar” worker was reduced to the execution of predetermined and well-regulated procedures.

Back to Foucault, who deliberated on different forms of power and authority in various social contexts. Foucault referred to western societies from the middle of the 18th century to the middle of the 20th century as "disciplinary societies", wherein the pairing of the individual and the institution is of central importance. In disciplinary societies, the individual is drawn into various institutions throughout his or her life; and is released again to become embedded in another institution. A family, an educational institution, military service and ultimately a job in a factory or an office. Meanwhile, during the course of his or her life, the individual may spend time in a hospital or psychiatric clinic; occasionally time is spent in prison. Each of the above-listed institutions enacts its own system of rules, be it written or unwritten, to which the individual is subordinate. To Foucault, the “Panopticon”, as conceived of by the British philosopher Jeremy Bentham, was the architectural manifestation of disciplinary society. This concept of a prison, designed around 1800, envisioned a circular structure of prison cells, wherein windows on both sides provided for maximal transparency. In the center of this ring-shaped building was to stand a tower - housing a guard who, from this central position, could monitor all prisoners. This architectural array was meant to install absolute efficiency: Even if the guard was absent, the possibility of his or her presence would lead the inmates to take over the guard's task; they would discipline themselves to conform to the rules of the institution.

The pertinence of Foucault’s reference to panoptic power structures becomes clear when looking at the evolution of the disciplinary society into a society of control, starting around the middle of the 20th century (Deleuze, 1992). In the chapter “An ethics of surveillance” (Bauman & Lyon, 2013, p. 163), Bauman speaks of “feedback loops” that were developed in the context of industrial production and became the modus operandi of the society of control. A supervisory system observes and collects data and upon an individual’s noticing or being informed that he or she is being observed, the circle is complete: knowing that he or she is being observed, the individual adjusts his or her behavior accordingly to conform to the standards of the respective institution. The institutions of the disciplinary society remained and disciplinary and controlling power from thereon went hand in hand. The part of such systems that defines “normal” or “desired” behavior, both in relation to general morality as well as to ethics of work or productivity, also holds the power of control: To this end, a wide variety of data is being collected. Not only many public places, but also most of the larger institutions are nowadays equipped with cameras. Zuboff (1988) describes this complementation of disciplinary and controlling forces without referring to the term “control” when she interconnects “Panoptic Power” and “Information Technology”. Today, there is no need to build towers for a permanent monitoring of individuals – minuscule cameras are available at a prize less than € 30.00. Zuboff states that:

“Information systems that translate, record, and display human behaviour can provide the computer age version of universal transparency […] Such systems can become information panopticons that, freed from the constraints of space and time, do not depend upon the physical arrangement of buildings […].” (Zuboff, 1988, p. 322)

Around 130 years after the rise of Taylorism, Amazon is one of the companies that are taking the Taylorian ideas into the modern age. Small-scale division of labor and a breakdown into specialized locations for packaging, sorting and dispatching make it possible for orders to be delivered on the very day of purchase. When it comes to employee selection, Amazon uses algorithms that estimate a prospects’ eligibility. Furthermore, there has been a plethora of scandals (Canales, 2020) surrounding the issue of “employee monitoring”. For example, Amazon used employees’ social media activities to anticipate complaints about working conditions and tendencies towards the formation of unions.

Where Taylor had to use means of direct human observation, such as measurement tape and a stopwatch, companies like Amazon can now resort to the help of modern technology and artificial intelligence. Throughout the corporate history, Amazon has filed a large number of patents. Amongst a multitude of patents, one of the more striking examples is a bracelet (Cohn, 2018, Patent No.: US 9,881,276 B2), which tracks employees’ hand movements and prompts them towards the correct parcels via vibratory signals. Praised as a gadget that facilitates work, its true value lies in the fact that it can monitor and store data on dimensions of interest to Amazon, such as working hours, task efficiency and breaktime.

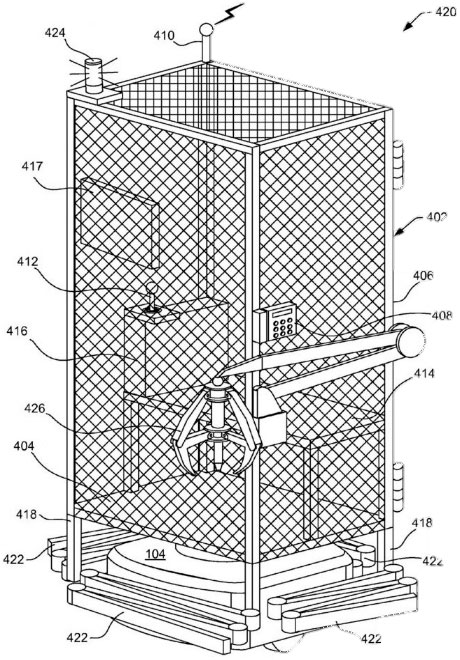

Another such patent, by now retracted supposedly due to a societal echo of ethical concern, is what is now known under the keyword “worker cage”. Amazon itself mentions the word “cage” in the original text of the patent: “[…] a cage-like structure […]” (Wurman et al., 2016, p.18). What was later referred to as the “cage” in the media is only a small part of a larger whole.

The “cage” is a system of transportation which, as a part of an automated workplace, allows for the safe transportation of a human employee in an environment in which robotic systems do most of the work. The “cage” is designed to protect employees from moving machinery in an automated environment. The route of transportation is specified and predetermined, like everything else at this future workplace, by a “management module”. The separation of the different types of work as described in Taylorism; the “physically operating” versus the “mentally organizing”, is given here. While the management module represents the organizational level, the worker in the “cage” represents the operational level. Specialists equipped the management module with artificial intelligence and programmed it such that the plan of procedures, as devised by the managers, is implemented.

It recognizes errors that constitute deviations from this plan and indicates them. The operating employee is reduced to the physical correction of such errors: Basic repair work, maintenance and replacement of weary parts fall into his or her responsibility. It goes without saying that these operations are meticulously documented to then be optimized.

The abovementioned exhibition “Mine” has this “cage” at its center: Denny has built the original cage as a static, non-functioning model by using the original plans. Denny himself describes the “cage” as a “[…] sculptory description of a kind of relationship between human labor and different types of machinic groups […] a very confronting object.” (KunstsammlungNRW, 2020).

Denny's decision not to interpret but to reproduce the patent as precisely as possible shows his intention to let it speak for itself. On the one hand, the close-meshed wire can indeed be understood as a means to occupational safety – Amazon speaks of a “structure configured to Substantially prevent the user from Sticking an appendage through the enclosure, such as an arm or leg of the user” (Wurman et al., 2016, p. 18) - on the other hand it represents the classic material of which cages are constituted. Denny leaves the "cage" empty - thereby prompting the viewers to imagine themselves sitting inside the cage. In the original patent, numbers serve to index different functional features of the cage. Denny uses a minimal approach by rebuilding both the figures and the index lines in thin metal. What effect does the missing of the information that is indexed by these numbers have on the viewer?

Each number raises questions that remain unanswered and open for speculation. Denny thus forces the viewer to question and scrutinize what he or she is confronted with. A specification of color cannot be found in Amazon's patent. Denny opts for a white version before a dark background in the Düsseldorf exhibition. What do we associate with the color white? The associations of sterility and cleanliness stand for the avoiding of (human?) error, mistakes and blemishes. Futurism, transparency, innocence, and neutrality are other terms that come to mind. On the contrary, the title “Mine” evokes associations of dark corridors, of dust and the opposite of sterility and transparency.

The cage as a part of an automated workspace and as constructed and presented by Simon Denny can further be interpreted as the architectural inverse of the surveillance as proposed by Bentham (i.e. a “guard” in the center, the “guarded” around the center). Although there is still an “inmate” - he is no longer a prisoner but an occupant; a human remnant moving through the center of an automated system. The observing force is no longer positioned in the center, but is everywhere around the center, universal, so to speak. Cameras are filming from every corner, while machines collect and save data. Denny reproduces this inversed panopticon and the potential trepidation that it may evoke in the exhibition room as the “cage” stands, illuminated from above, in the center of the room with the visitors moving around it. When referring back to real employees in real Amazon warehouses one may even interpret Dennis “cage” in its most literal and symbolic sense – the employee is a prisoner of his or her limited abilities; surrounded by machines that perform what used to be his or her job in a more competent manner thereby demonstrating his or her weak competitive position. The worker is trapped in his or her limited human ability.

Denny’s self-conception is that of a critic of capitalism and indeed, in reference to the above interpretation, the “cage” also symbolizes a crystallization of a class society. In the future, education will become ever more important, as physical labor will successively be delegated to machines. Those who do not acquire the ability to program or instruct “management modules” remain enclosed in the cage of limited abilities. When relating Denny’s work to the panopticon proposition, a literal interpretation of the cage as a symbol of confinement derives further validity if considered in light of an idea of philosopher Zygmunt Bauman. In discussion with sociologist David Lyon, Bauman refers to the Panopticon as a “Ban-opticon” (Bauman & Lyon, 2013, p. 117), thereby emphasizing his opinion of the potential by-product of all surveillance: Contrary to military surveillance, which oftentimes ultimately results in the death of an individual, he believes that the controlling, sanctioning and categorization of individuals (credit rating, eligibility in the job market etc.) based on relevant data, if telling a tale of inadequacy, result in their social death (receiving no loan, finding no job etc.).

In the middle of the inorganic sculpture with its horizontal and vertical lines, sits the life-size outline of a songbird. When scanned with a device which is provided upon entering the exhibition, a barcode on this element of the sculpture produces the chirping of a bird and a fluttering bird can be seen on the screen of the device. The viewer is informed that this bird, the "King Island Brown Thornbill", will most likely be extinct in the coming 20 years. The extent to which humanity may be a dying species within its classic modes of living and working is a question that comes naturally, especially as the bird-module is installed where the worker is to be seated in the original design.

When looking at the bird, the viewer may also be reminded of the work-field of mining: In many mines, miners brought a canary bird underground. If the birdsong stopped or the bird even passed out or died, this served as a warning signal of impending monoxide poisoning. The image of a classical “birdcage” is also quickly evoked: The chirping bird in the cage, at the place where the worker is to be seated, confronts us with our moral indecision and our anthropocentrism in dealing with nature: The locking of a person in a “cage” provokes ethical debate whereas we believe that caging millions of birds as pets is normal and appropriate. As such, the birdcage is a symbol that may even cause its contemplators to imagine themselves as the future pets of intelligent and independent robots.

So tracked! Is the life of thousands of men, women, and young persons at the start of the new millennium. It seems as if the nature of our stress has changed in modern times. While, 150 years ago, people came home exhausted as they could not keep up with the demands of the changing world of work, the nature of our exhaustion is different today. The knowledge of the ubiquitous collection and analysis of our data exhausts us. At a time when we all carry a smartphone in our pocket, most of us are “linked-in”. Today, most of us carry their own panopticon with them and in the brave new world, he who refuses to be transparent sorts himself out, as whoever is not “linked-in” is “left-out”.

In times of datafication, surveillance and the emerging of what is often referred to as “Industry 4.0”, Denny’s cage is a symbolic yet powerful seismograph of the current state of development. It vividly highlights two themes that are inherently tied to the topic of “artificial intelligence”: peoples fearing of losing their job due to being replaced by intelligent machines and the concern about the omnipresent monitoring and storing of data. Not only in the case of Amazon do these topics belong together. Optimists see the birth of a new generation of machines as slaves to the human race, such that humanity will be liberated from the strain of physical labor and free to live up to its creative potential. Hence, some even anticipate a bloom of the arts. The pessimistic, on the other hand, fear that humans might become secondary; existing as quaint “pets” to artificial intelligences, that will become so intelligent that they will continue to develop without human intervention. Whatever the future may hold; we should be alert to as many scenarios as possible. Quite often it is artists like Simon Denny who help us see the world from different perspectives and who capture its’ ability to change.

References

Bauman, Z., & Lyon, D. (2013). Daten, Drohnen, Disziplin: Ein Gespräch über flüchtige Überwachung. Suhrkamp Verlag.

Blayney, S. (2017). Industrial fatigue and the productive body: The science of work in Britain, C. 1900–1918. Social History of Medicine, 32(2), 310-328.

https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/hkx077

Canales, K. (2020, September 17). 2 US Senators just demanded Amazon stop spying on its workers via social media after news surfaced that the tech giant was monitoring drivers' plans to protest or strike. Business Insider. Retrieved from

https://www.businessinsider.com/senators-demand-amazon-stop-spying-drivers-social-media-2020-9?international=true&r=US&IR=T

Data. (n.d.). In Cambridge Essential English Dictionary. Retrieved from

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/essential-british-english/data

Deleuze, G. (1992). Postscript on the Societies of Control. October, 59, 3-7. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/778828

Jonathan Evan Cohn. (2018). Ultrasonic Bracelet and Receiver for Detecting Position in 2D Plane. United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved from

https://pdfpiw.uspto.gov/.piw?PageNum=0&docid=09881276&IDKey=4B77C237270E%0D%0A&HomeUrl=http%3A%2F%2Fpatft.uspto.gov%2Fnetacgi%2Fnph-Parser%3FSect2%3DPTO1%2526Sect2%3DHITOFF%2526p%3D1%2526u%3D%2Fnetahtml%2FPTO%2Fsearch-bool.html%2526r%3D1%2526f%3DG%2526l%3D50%2526d%3DPALL%2526S1%3D9881276.PN.%2526OS%3DP

Keegan, M. (2019, December 2). Big Brother is watching: Chinese city with 2.6m cameras is world's most heavily surveilled. The Guardian.

KunstsammlungNRW, (2020, September 05). Artist Talk: Simon Denny & Boaz Levin [Video]. YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NOKgCCKhNgc

West, S. M. (2017). Data capitalism: Redefining the logics of surveillance and privacy. Business & Society, 58(1), 20-41.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650317718185

Wurman, P. R., Barbehenn, M. T., Verminski, M. D., Mountz, M. C., Polic, D., Hoffman, A. E., Allard, J. R., & Nice, E. B. (2016). System and Method for Transporting Personnel within an Active Workspace. United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved from

https://pdfpiw.uspto.gov/.piw?Docid=09280157

Zuboff, S. (1988). In the age of the smart machine: The future of work and power. Cambridge University Press.